Nightfall!

Continuing our journey into French spectral music, NIGHTFALL! opens with Grisey's Stele for two percussionists. The Florida Premiere of Dave Maric's Nascent Forms (an enSRQ Co-Commission) precedes David T. Little's Haunt of Last Nightfall, a striking and provocative 'ghost play' for four percussionists and electronics, remembering the 1981 El Mozote massacre in El Salvador.

Program

| Gerard Grisey | Stéle (1995) 6’ |

| George Nickson and Ye Young Yoon, percussion |

| Dave Maric |

Nascent Forms (2019) 17’ (enSRQ Co-Commission and Florida Premiere) |

| George Nickson and Charlie Rosmarin, vibraphones Mike Truesdell and Ye Young Yoon, marimbas |

| David T. Little |

Haunt of Last Nightfall (2010) 31’ for percussion quartet and electronics a ghost play in two acts |

|

ACT I I. Curtain, El Mozote - II. Between The Hammer and The Anvil - III. Last Nightfall - IV. Line Up/Face Down - V. Coda: And there was evening… ACT II VI. ...and there was morning - the Second Day. - VII. Smoldering Hymn - VIII. Prayer (for No. 59) - IX. Postlude: The Girl on La Cruz |

| George Nickson, Charlie Rosmarin, Ye Young Yoon and Mike Truesdell, percussion |

Gerard Grisey (1946-1998)

Gérard Grisey was born in Belfort on June 17th, 1946. He studied at the Trossingen Conservatory in Germany from 1963 to 1965 before entering the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique in Paris. Here he won prizes for piano accompaniment, harmony, counterpoint, fugue and composition (Olivier Messiaen’s class from 1968 to 1972). During this period, he also attended Henri Dutilleux’s classes at the Ecole Normale de Musique (1968), as well as summer schools at the Accademia Chigiana in Siena (1969), and in Darmstadt with Ligeti, Stockhausen and Xenakis in 1972.

He was granted a scholarship by the Villa Medici in Rome from 1972 to 1974, and in 1973 founded a group called L’Itinéraire with Tristan Murail, Roger Tessier and Michael Levinas, later to be joined by Hugues Dufourt. Dérives, Périodes and Partiels were among the first pieces of spectral music.

In 1974-75, he studied acoustics with Emile Leipp at the Paris VI University, and in 1980 became a trainee at the I.R.C.A.M. In the same year he went to Berlin as a guest of the DAAD (Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst), and afterwards left for Berkeley, where he was appointed professor of theory and composition at the University of California (1982-1986).

After returning to Europe, he has been teaching composition at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique in Paris since 1987, and holds numerous composition seminars in France (Centre Acanthes, Lyon, Paris) and abroad (Darmstadt, Freiburg, Milan, Reggio Emilia, Oslo, Helsinki, Malmö, Göteborg, Los Angeles, Stanford, London, Moscow, Madrid, etc.)

Among his works, most of which were commissioned by famous institutions and international instrumental groups, are Dérives (1973-1974), Jour, contre-jour (1978-1979), Tempus ex Machina (1979), Les Chants de l’Amour (1982-1984), Talea (1986), Le Temps et l'Ecume (1988-1989), Le Noir de l'Etoile (1989-1990), L’Icône paradoxale (1993-1994), Les Espaces Acoustiques (1974-1985 - a cycle consisting of six pieces), Vortex Temporum(1994-1996), Quatre chants pour franchir le seuil (1997-1998).

Gérard Grisey died in Paris on 11 November 1998.

Stéle (1995)

(Posted by Ricordi 27 June 2014: Fabien Lévy writes about Stèle by Gérard Grisey)

15 years ago, on the 11th of November 1998, Gérard Grisey died suddenly at the age of 52. I will remember for a long time that Wednesday when the news reached us, his students at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique in Paris. (I was then in the last year of the composition class and was supposed to be taking my finals some months later.) As usual, we had had a class the preceding Saturday, and Grisey mentioned for the first time the death of Messiaen, his composition teacher. By another strange and sad chance, which for a long time made me think it was intentional, Grisey was in the process of writing the Quatre chants pour franchir le seuil (Four Songs for Crossing the Threshold), four magnificent pieces on the theme of death.

Four years previous, on almost the same date (29 November 1994), the young composer Dominique Troncin had died at the age of 33, after a long illness. Dominique had also been important in my life because when I was still only an amateur composer and following scientific studies, he suggested I should go and study at the Conservatoire Américain de Fontainebleau, a summer school founded before the war by Nadia Boulanger and intended particularly for American students. That year (1990), Dominique was acting as coordinator and teacher of analysis, and Tristan Murail and André Boucourechliev were teaching composition there. A great coincidence, because ten years later I was to become a colleague of Tristan Murail at the Columbia University in New York, and I myself would teach composition at the American conservatory at Fontainebleau from 2007 to 2010.

After the death of Dominique Troncin, the ensemble Fa, directed by Dominique My, organized a concert in his honor at Radio France, and numerous composers wrote new pieces for the occasion. Stèle (1995) by Gérard Grisey was one of these premieres in homage to Troncin, and stood out from the series of rather anonymous pieces by its originality and depth, which was even more surprising given that the instrumentation of the piece was more than limited: just two bass drums!

This was not Grisey’s first piece for unpitched percussion. At the end of the 1970s, when the word ‘spectral’ began to be used to define the group to which he belonged and when the frequency techniques used by this group were being established, Grisey, refusing as always to follow the herd, decided to write an unpitched piece. This was Tempus ex machina (1979) for six percussionists. In 1991 there followed le noir de l’étoile, for six percussionists and the sound of a live pulsar broadcast. (The premiere, 16 March 1991 in Brussels, began at 5:00 p.m.; the signals from the pulsar [0329+54] being expected at 5:45 p.m. precisely.) However, both pieces required a generous number of instruments.

Stèle, by virtue of its extremely limited instrumentation, presents quite another constraint. One has briefly to resume the history of unpitched percussion to understand the historic ingeniousness of the piece. Percussion instruments have always been secondary accessories in Western music. Exported by the Turks and their armies of janissaries (i. e. Mozart’s Turkish March), for a long time they did nothing in the orchestra but mark the accents and the tuttis, and accompany ‘pitched’ music. Noise was in effect a stranger in Western music. It is equally surprising that in the West each instrumentalist in the orchestra was highly specialized, but that the musicians called ‘percussionists’ were expected to play everything that the others did not play, from xylophone to whistle to slide flute, passing by the wind machine, cymbals and timpani. The percussionists in effect did the ‘odd-jobs’ of the orchestra, almost vilely subservient. The first work for percussion alone only appeared in the first third of the 20th century, with Ionisation (1933) by Varèse (1883–1965), a composer influenced by the noisy theories of the Italian futurist, Luigi Russolo. This is a long way from the very ancient and elaborate practices of unpitched percussion in most other cultures, whether they be in Africa, America, or Asia. Another oddity in our Western culture is that, while many cultures use a minimal number of percussion instruments with myriad colours and performing techniques (for example, the famous tabla of north India), Western composers use each instrument more or less to produce a single sound: the bass drum goes ‘boom’, the side drum ‘ping’, the cymbal ‘tschhh’, and the gong ‘doon’—a profusion of means but very little subtlety, as so often in the West . . . .

Stèle is extremely innovative and ingenious in this respect: two bass drums, one of medium size and one large. The latter is draped with a string of wooden beads to ‘dirty’ the sound, a little like those African instruments that one prepares to make their sound less harmonious and more rich (little balls of spiders’ webs to make wind instruments buzz, little metal discs for the sanza). As for the Indian tabla or mridongam, different places on the stretched skin of the bass drum are used in Stèle to vary the colours. Finally, six sticks of different hardness, thickness, and material (wood, felt, bundled dowels of the ‘hot rod’-type) are used as well as two types of brushes (which scrape the skin in order to ‘inhabit’ the silence). The bass drums also have mutes to dampen and modify their sonority. The two instruments are thus used to their full coloristic capacity.

The composition itself is equally ingenious: the instrumentalists have to be placed apart to create echo games, ritualistic effects, slow and funereal patterns which become dramatic, in rhythmic and polyrhythmic writing that is extremely precise, clear and effective.

At a time when so many composers were or are creating ‘contemporary music’ without originality, hiding their lack of subtlety with a fake, superficial, seemingly ‘dissonant’ complexity, Stèle, like the rest of Grisey’s work, remains a model for composers: the piece is highly inventive and deep, musically. It uses minimal means that are explored in an ingenious fashion and in their entirety. Grisey was in fact a demanding composer, passionate about good music, and in this sense modest. He refused to make a career for himself (only one CD had been recorded at the time of his death) or to caricature himself. He worked every day but only wrote around one piece every two years. But what works!--unique, single-minded. He required his pupils also to take real risks, ones which were audible even if they would disconcert the public or contradict the ‘contemporary music industry’. He told us to compose and not to ‘produce’; always to strive to give of our best, even to the point of surprising ourselves.

Some months after his death, we all went to London to hear the premiere of Quatre chants pour franchir le seuil. While we expected to hear a piece in the manner of his last works, Vortex temporum or Stèle, Grisey renewed himself yet again and presented us with a last composition lesson, posthumously and unforgettably.

— Fabien Lévy, 11 November 2013

Dave Maric (b. 1970)

Dave Maric is a British composer and performer of acoustic and electronic music who has created numerous works for the concert hall, stage and film. He has regularly worked with classical musicians, jazz musicians, experimental electronics, free improvisers, folk musicians, art-rock musicians, singer-songwriters, poets, visual/performance artists, choreographers, animators and filmmakers, and has also curated numerous events featuring stylistically varied music - often in conjunction with other artistic disciplines.

During the 1990s he frequently performed with artists and ensembles in the jazz, rock and classical worlds ranging from projects with acclaimed musicians such as Marc Ribot to various contemporary music ensembles such as the London Sinfonietta. In this period he also worked for a number of years as composer Steve Martland's artistic assistant whilst also being a key member of his ensemble, the Steve Martland Band. During this period his interest in composing began with formative experiments straddling the worlds of electronic dance music, jazz and contemporary classical music. But it wasn't until 2000 that he began composing for the concert hall and his first piece (Trilogy, a solo work for the percussionist Colin Currie) inspired a flurry of new chamber works for acclaimed classical soloists, including violinist Viktoria Mullova and pianists Katia and Marielle Labèque. Lucerne Festival, Radio France, Cheltenham Festival, Norwegian Radio Orchestra and BBC Radio 3 have all since commissioned works from Maric, including pieces for l'Orchestre National de Montpellier, trumpeters Håkan Hardenberger and Ole Edvard Antonsen and guitarist Fred Frith. Maric has an ongoing artistic collaboration with Colin Currie (and subsequently other solo percussionists) through regularly developing new works for percussion (so far twelve works have been premiered by Currie alone) which have since become standard repertoire for many students and soloists internationally. He also regularly performs in the Colin Currie Group (performing the music of Steve Reich). Maric often works with jazz musicians and free improvisers as performer and composer; including Decade Zero, a large scale composition for the acclaimed jazz trio Phronesis with the Engines Orchestra, and an electro-acoustic improvisation project with composer/instrumentalist Elo Masing called Vicious Circus. He has also made numerous recordings focussing on his multi-stylistic compositions and improvisations; most recently his second and third solo albums: Musica Antiqua Tronica and From Thin Air.

Maric has also worked with a range of other art forms from spoken word to video art, performance art, animation, shadow puppetry, film, animation and dance where he has produced a wide variety of music ranging from short electronic pieces to full evening orchestral scores. These include works for the Theatre of Dolls, Royal Opera House Covent Garden, Channel 4 (UK), Northern Ballet Theatre, Finnish National Opera and the Bern Ballet. (Dave Maric)

David T. Little (b. 1978)

David T. Little (b. 1978) is “one of the most imaginative young composers” on the scene, a “young radical” (The New Yorker), with “a knack for overturning musical conventions” (The New York Times). His operas JFK (Fort Worth Opera), Dog Days (Peak Performances/Beth Morrison Projects), and Soldier Songs (Prototype Festival) have been widely acclaimed, “prov(ing) beyond any doubt that opera has both a relevant present and a bright future” (The New York Times). Recent/upcoming works include Ghostlight—ritual for six players for eighth blackbird/The Kennedy Center, AGENCY (Kronos Quartet), CHARM (Baltimore Symphony/Marin Alsop), Hellhound (Maya Beiser), Haunt of Last Nightfall (Third Coast Percussion), a new opera commissioned by the MET Opera/Lincoln Center Theater new works program, and the music-theatre work Artaud in the Black Lodge with Outrider legend Anne Waldman (Beth Morrison Projects). His music has been heard at Carnegie Hall, LA Opera, the Park Avenue Armory, the Bang On A Can Marathon, and elsewhere. Educated at University of Michigan and Princeton, Little is co-founder of the annual New Music Bake Sale, has served as Executive Director of MATA, serves on the Composition Faculty at Mannes-The New School and Shenandoah Conservatory, and is Composer-in-Residence with Opera Philadelphia and Music-Theatre Group. The founding artistic director of the ensemble, Newspeak, his music can be heard on New Amsterdam, Innova, and VisionIntoArt labels. He is published by Boosey & Hawkes.

Haunt of Last Nightfall

I think a lot about ghosts. Not so much in the literal sense of sheet-wearing specters, but rather, of things ghostly in function. That is, things that remain behind as the fleeting evidence of what once was. For some reason - perhaps for the same reason as the monk of old’s memento mori - I have always felt the need to surround myself with these kinds of ghosts. The studio where I compose, for example, is full of mementos: objects from past projects, trinkets from past travel, and most notably, old photographs. I have collected these antique photos for about 10 years, not for the photographic quality - I know little about photographic history - but for the mysterious stories they may tell of the people whose images they hold. They are, in a sense, my ghosts.

They lived full lives once upon a time, these people. They had husbands, life, joy and pain. They were no different, really, then you or me. And it here they are, preserved in a single moment - perhaps the only evidence of their existence - itself gradually fading. I have no idea who any of them are, but it doesn't seem to matter. In a certain sense, they each are all of us.

Although this peculiar passion of mine is at the core of this composition, it's not really what the piece is about. Rather, the “ghost” here is an atrocity that happened long ago, the memory of which I just can't seem to shake. Specifically, it is the massacre in El Mozote, El Salvador, December 10th through 12th 1981, in which an entire village was erased by US Military-trained Salvadoran government forces, with American-made and provided arms.

Now, I have no interest in getting on a soapbox about El Mozote, or related issues; that is, in fact, the last thing that I want. It's just that since reading about the massacre - first in Bob Ostertag’s Creative Life, and later in Mark Danner's The Truth about El Mozote - I have been plagued by two questions: first, how did I never know that this had happened? (The answer to this is fascinating and upsetting.) And second, why am I completely unable to get it out of my mind; to move on? It haunts me. It has been, for the last fifteen months, my ghost.

I cannot forget the story of the young boy - now only known as “No. 59” - who was lucky enough to have a toy, though it could not protect him from the bayonet. I cannot forget the separation of families that happened on the morning of the second day - men to the right, women and children to the left - reminiscent of another atrocity, forty years earlier. I cannot forget the girl on La Cruz, a local hill, who is said to have sung a hymn as soldiers repeatedly raped her. Legend holds that even after they murdered her, her body kept singing, stopping only when they cut off her head. I cannot forget that this village, innocent by virtually every account, was slaughtered, caught in the crossfire of a stupid ideological battle.

I would never say something so boldly reductive as “their blood is on our hands.” We all know that scenarios like these are neither that simple, nor all that unique. But I do know that I've been unable to shake this ghost, and consequently felt that I had no choice but to write this piece.

We know what shapes us, and whether I like it or not, I now know this.

David T. Little

October 9, 2010

Special Thanks To:

Sam Nelson

Greg Chestnut

First Congregational Church

Taylor Rothenberg-Manley

Hojoon Kim

Board of Directors

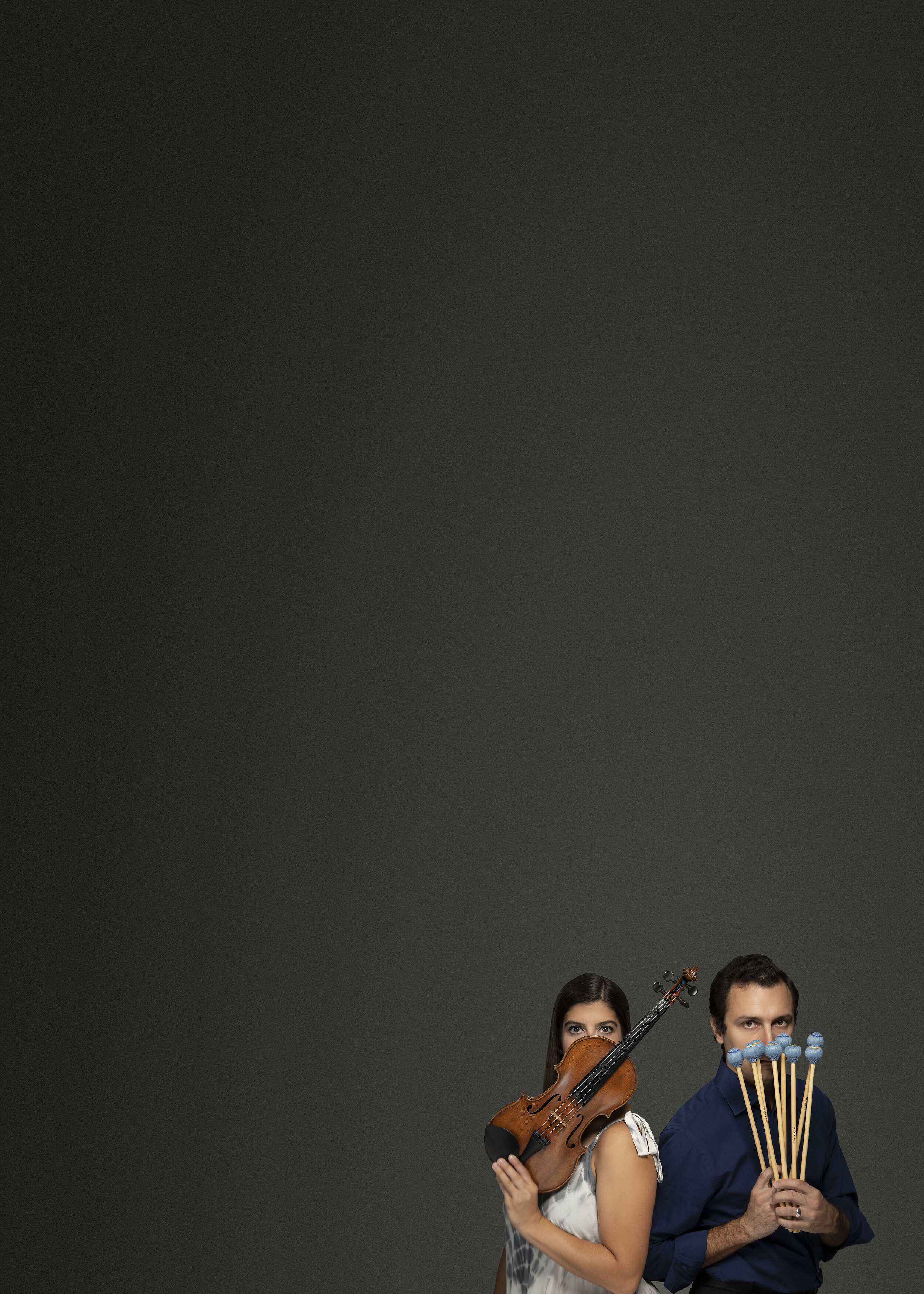

George Nickson: Chair and co-artistic director

Samantha Bennett: Vice-chair and co-artistic director

Justin Vibbard: Secretary

Eric Dean: Treasurer

Brian Boyd

Linda Z. Buxbaum

Stephen Fancher

Joan Golub

Pat Michelsen

Joe Seidensticker